Eugenio Carmi and Industry

Artistic consultant to the Italsider steelworks: art enters the factory and the factory produces culture (Watch a documentary video).

In 1956 Eugenio Carmi became artistic consultant to Cornigliano, the Genoese steelworks where Gian Lupo Osti was secretary-general. In accordance with Schumpeter’s and Olivetti’s management theories, Osti was convinced that a factory should not only be a source of material goods, but also and above all — thanks to its enormous economic potential — a producer of culture and a means of encouraging civil progress. An enlightened manager, he was in charge of a programme for relaunching the steelworks, which, like other Italian firms, had received funds from the Marshall Plan in the post-war period: together with an innovative industrial plan, Osti immediately sought to promote a cultural policy closely linked with both the intellectual and contemporary artistic milieux and the surrounding area, and this was why he decided to make use of an artist’s sensibility. Osti invited Eugenio Carmi to create a new, progressive corporate image. In 1961 Cornigliano merged with Ilva to form Italsider, which included other steelworks. Under Osti’s management, with Carmi, Italsider became a powerhouse of ideas and culture. At the same time Eugenio Carmi’s artistic work was extremely fruitful, leaving a strong mark on the factory, which, in its turn, influenced the artist’s poetics. In parallel with this, Carmi was one of the leading exponents of the international style in the graphic arts.

Rivista Italsider, a vehicle for art and culture

Exhibitions: far from academicism, production and provocation

Corporate communication: the language of abstraction and the incursion of colour

Carmi’s contribution to the graphic arts in the 1950s and 1960s

Rivista Italsider, a vehicle for art and culture

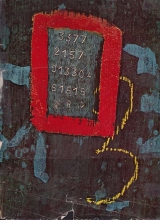

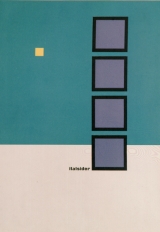

Carmi was immediately given the task of communicating with the public outside the industry through a campaign in the leading national and local newspapers. The idea was to show — using an avant-garde visual language — that steel could be the driving force behind the country’s modernization. In fact, he used the superimposition of negatives for the images and simple graphics with geometric insertions. For internal corporate communication aimed at the firm’s employees, a house organ, the Rivista Cornigliano was created. For the editing of the magazine, Carmi, who was its art director, enrolled the services of a young journalist working for ANSA (the Italian national press agency), Carlo Fedeli (in 1956 he became the head of the firm’s press office) with whom he worked on the layout of the magazine. This was the start of an extremely fruitful collaboration between Osti, Carmi and Fedeli — who shared the same cultural and social objectives and the same enthusiasm — that was to continue over the years. ‘I was very ambitious,… [it was necessary to create] an image for the steelworks that was modern and also strong, especially from a cultural point of view. This was what interested not only me but also Osti and Fedeli;… I started to design all the firm’s graphics, inviting numerous artists that I knew in Italy and elsewhere in Europe to create the covers of the magazines: they seemed to be the covers of an art magazine, while, in reality, they were those of a house organ…. This is because the firm’s image was always given great importance.’ From 1961 to 1965 Carmi’s industrial experience continued in a new company. On 27 April 1961 Cornigliano merged with another steel group, Ilva, to form Italsider SpA, which incorporated the Ligurian firm with other Italian steelworks — Bagnoli, Taranto, Marghera, Lovere, Savona, Novi Ligure, Piombino, Trieste, San Giovanni Valdarno and Campi — all under the central management of Gian Lupo Osti in Genoa. Eugenio Carmi and Carlo Fedeli — with whom he later founded the Galleria del Deposito — expanded and renewed the magazine, now known as the Rivista Italsider. Intended not only for the employees of the eleven steelworks, but also for a wider public, it became a publication with a high cultural profile and the contributions of a growing number of internationally renowned artists, intellectuals and photographers. The magazine’s graphic design was changed and one of the most important elements was the cover: formerly featuring the steelworks and its products, it now reproduced the works — some of them specially commissioned — of international contemporary artists, both well established and up and coming.

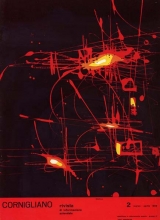

In the course of their publishing activity for industry, Eugenio Carmi and Carlo Fedeli also produced books such as Immagine di una città (Image of a city, 1958) and Immagine di una fabbrica (Image of a factory, 1959). Carmi engaged the Swiss photographer Kurt Blum to illustrate the books, believing him to have the sensitivity necessary for the understanding and interpretation of the threatening yet fascinating essence of industry, over and above its predictable appearance. For the cover of the second elegant photographic book, Carmi once again chose a non-representational design, creating a work that, through the synthesis of red and black and a few abstract signs immediately evoked impressions of a steelworks. This was the period of his enamel paintings on steel, which he started to produce in 1958 and 1959. In 1963 Eugenio Carmi conceived a publishing programme that, in line with the cultural policy of the Rivista Italsider, once again constituted the abolition of the boundary between the iron and steel industry and the world of contemporary art. The book I colori del ferro (The colours of iron) was published by Italsider as a Christmas gift. Carmi added to — and alternated with — a series of pictures by important photographers, such as Kurt Blum, Paolo Monti, Ugo Mulas, Federico Patellani and Lando Civilini, photographs and technical macro-photographs of materials and industrial views in a new, sophisticated aesthetic and semantic dialogue. An essay by Umberto Eco introduced the book, also stressing the importance of Carmi and Fedeli’s idea of not entrusting the captions to an art critic but rather to an engineer, Gino Papuli, who, with a wealth of interesting details regarding the materials and manufacturing processes, provided another key to their interpretation.

Using an idea of his, Carmi made a documentary film in collaboration with Kurt Blum, who was chiefly responsible for it. In L’uomo il fuoco il ferro (Man fire iron) (watch the video), Blum — through his direction and editing, clearly inspired by the Russian cinema of the 1920s and French Symbolism — created a monstrous, inhuman image of the steelworks, albeit an aesthetically moving one. The workers appear to be faceless walk-ons threatened by flows of molten steel and huge machinery in motion with which they have to interact every day. Prokofiev’s ‘Diabolic Suggestions’ stress the dramatic force of the images. In this case, too, reality is represented in its abstract forms. The film won first prize in the documentary section of the Venice Film Festival of 1960.

Exhibitions: outside the Academy, Production and Provocation

The Corniglia steelworks in Genoa also sought to set the standard for the quality of the urban environment both as regards the factory itself, housing and town planning in a general sense. In March 1959, at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome, it organized an exhibition entitled ‘Forme e tecniche dell’architettura contemporanea’ (‘Forms and Techniques of Contemporary Architecture’), the executive committee of which comprised — in addition to Gianlupo Osti and Eugenio Carmi — Giulio Carlo Argan, Bruno Zevi, Palma Bucarelli and Luigi Moretti.

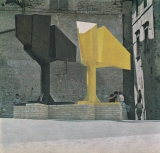

The exhibition was divided into two sections: the first featured one of the greatest architects of the twentieth century, Le Corbusier; the other, entitled Lamiere d’acciaio nell’architettura. Costruire nel nostro tempo (Sheet-Steel in Architecture. Building in Our Times), curated by Konrad Wachsmann, was devoted to the new construction techniques, prefabrication and industrial materials capable of renovating the forms of modern life. Carmi’s enamel paintings — Architettura immaginaria (Imaginary Architecture) was reproduced on the cover of the exhibition catalogue and poster — and works by Emilio Scanavino were displayed next to the plans, models and photographs.

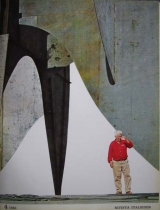

When the Cornigliano steelworks merged with Italsider everything became bigger in scale, not only from the productive and economic points of view, but also — and this was what most interested Carmi, Fedeli and Osti — with regard to cultural promotion. With the new national dimension, there were more opportunities for public events, publications and exhibitions and, in fact, this was a period in which Italsider supported high-profile cultural activities, establishing itself as an experimental, anti-academic organization. Eugenio Carmi played both a centripetal and a centrifugal role with regard to industry: through his creative impulse, art entered the factory and, at the same time, the artist became a driving force on the Italian and international art scenes. As in the case of the Galleria del Deposito in Boccadasse, Carmi became a catalyst for talent. In 1962, on the occasion of the exhibition of Italian industry in Moscow, Carmi, with the support of Gianlupo Osti and the collaboration of the Galleria del Naviglio in Milan, arranged the participation of Italsider with a pavilion that offered, together with a room providing information about the company’s products, a show of contemporary Italian art. Defying the orthodoxy of Socialist Realism — there were, in fact, perplexed and polemical reactions on the part of the authorities in Moscow — he invited a series of artists (Ugo Attardi, Edmondo Bacci, Domenico Cantatore, Giuseppe Capogrossi, Giancarlo Cazzaniga, Guido Chiti, Flavio Costantini, Franco Gentilini, Achille Perilli, Giacomo Porzano, Emilio Scanavino, Libero Verzetti, Renzo Vespignani and Emilio Vedova) to participate, together with him, with a large-format work inspired by the world of work, which, in some cases, he specially commissioned on behalf of the company. The task of designing the exhibition installation was given to Bruno Munari, who created a totally black circular space with atmospheric top lighting. In the summer of the same year, as part of the 5th Festival dei due mondi (Festival of the Two Worlds) in Spoleto, Giovanni Carandente organized an exhibition there entitled ‘Sculture nella città’ (Sculptures in the City), an event that was as controversial as it was acclaimed and attracted the attention of the international press. Fifty artists from all over the world were invited to display their works in the urban space: for a brief period of time, the old palaces and squares became the setting for an open-air museum. The show was given financial and organizational support by Italsider. Originally the company was only expected to make a financial contribution, but Carmi and Fedeli proposed a more direct encounter between the activity of the artists and that of the steelworks, transforming the factory into a workshop of talent: Italsider placed at the disposal of ten of the sculptors selected by Carandente huge spaces in various factories and the collaboration of the workers so they could create large-format steel works that they could never have made in their own studios. David Smith worked in an abandoned factory in Voltri, Carlo Lorenzetti and Pietro Consagra chose Savona, as did Alexander Calder (who only sent a model of the work Teodelapio, which was made by the workers in the factory), Lynn Chadwick and Ettore Colla worked in Bagnoli, Beverly Pepper in Piombino, Arnoldo Pomodoro in Lovere and Nino Franchina in Cornigliano. Eugenio Carmi also participated with the sculpture All’Algeria (To Algeria), concerning which he subsequently recalled on various occasions above all the enthusiastic and constructive involvement of the workers.

Corporate communication: the language of abstraction and the incursion of colour

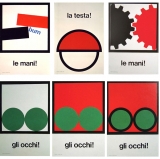

Eugenio Carmi was responsible for the firm’s corporate image, intervening in a series of initiatives undertaken by Osti’s office that were intended to improve the way workers experienced the factory. The industrial style that he created firstly for the Cornigliano steelworks and then for Italsider was based on the repeated use of geometric elements that, like a sort of trademark, characterized the factory’s external signage, all the material used by the staff (folders, box files and so on), press releases, brochures, gift wrapping paper and even the internal balance sheets. By adding the language of abstract art to all the factory’s products and, as his friend and colleague Carlo Fedeli pointed out, causing the incursion of colour into all the working environments, he redefined the spaces and modalities of the industrial system, drawing on his belief in the dignity of work and the liberating value of art as an active element in social life. In 1965 he designed eight signs focusing on quality that, printed on tin plate in the factories, bore a series of slogans with simple geometric elements, letters of the alphabet and colours on a white ground. For Carmi, the world of work was an important driving force behind his creativity. He was convinced that those working in factories needed not only aesthetic stimuli but also inspiring thought that was neither mechanical nor predictable. This was why, when asked to create a series of accident-prevention signs, rather than making use of the customary stereotypes, he turned things on their head: instead of symbolizing the danger itself, he drew attention to the part of the body needing protection, thus revolutionizing ways of communicating and establishing a more human relationship with those looking at the sign. In this case, too, the simple geometric forms, created in the six primary colours, represent the head, the eyes and the hands, stressed, with the visual energy typical of Carmi, by the word written in Helvetica.

Carmi’s contribution to the graphic arts in the 1950s and 1960s

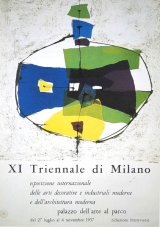

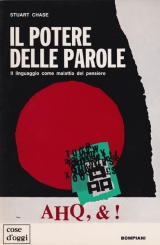

Eugenio Carmi (member of the Alliance Graphique International since 1954) made an important contribution to the Italian graphic arts of the 1950s and 1960s. Read a text in the Graphis magazine. Apart from his role at Italsider, already discussed at length above, Carmi was responsible for many visual communication works for firms large and small, including Esso. In addition to advertising, mention should also be made of his graphic works in the fields of publishing and culture in a more general sense. At the end of the 1960s he designed a series of book covers for the Bompiani publishing house. and in 1957 he won the single international prize for a poster at the 11th Milan Triennale.